David Russell Mosley

13 February 2014

On the Edge of Elfland

Beeston, Nottinghamshire

Dear Friends and Family,

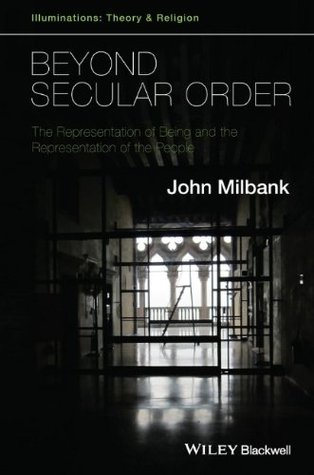

Since reading John Milbank’s latest book (which I’ve reviewed here), I’ve had King Arthur on the brain. You see, Milbank argues that kingship––by this he means a kind of monarchic rule that takes into account the one (monarchy), the few [oligarchy/aristocracy, and the many (democracy)––has a role that is simultaneously above and below that of the priest. This is because the priest is looking after our souls but the king looks after us now as we are and is a foreshadowing of how we will be in the life to come. In the course of this conversation Milbank then makes the provocative claim ‘If Christ is to return, then so too is Arthur.’ That is, kingship has a kind of christological and eschatological bent toward it (which is to say it is a picture of Christ’s dual roles as priest and king, and it foreshadows his return). Here is the passage in full to give you some context for my ruminations:

‘The tension therefore between priest and king is still more complex than theology has always allowed, and more genuine to the entire nature of Christianity than is usually recognised. The Christological conundrum of kingship means that the king is, for here and now, insofar as he is concerned with natural matters, ‘above’ the priestly function. But as regards matters pertaining to the ultimate welfare of our soul, the king is subordinate to the priest. Yet in a third sense the latter’s role is penultimate, not ultimate. As regards human‘spirit’, the whole person and the ultimate resurrection of the whole person, soul and body, the king and the concerns of kingship are symbolically more ultimate, since they are a remote foreshadowing of the eschaton. If Christ is to return, then so too is Arthur, so also Charlemagne, Frederick II and King Sebastian of Portugal (lost in battle against the Moors and one day to return to shore from the sea, where he is rumoured to wander over the waves)’ (Beyond Secular Order, 250).

The return of Arthur is something rather deep-seated in British mythology (I find it very interesting that the Portuguese have a similar notion about one of their kings). The notion of Arthur’s return begins with Geoffrey of Monmouth (a twelfth-century British priest) and his History of the Kings of Britain.  In the book, Geoffrey claims that Arthur was taken to Avallon after his final battle with his bastard son Mordred and was healed, he writes ‘And even the renowned king Arthur himself was mortally wounded; and being carried thence to the isle of Avallon to be cured of his wounds, he gave up the crown of Britain to his kinsman Constantine, the son of Cador, duke of Cornwall, in the five hundred and forty-second year of our Lord’s incarnation’ (History of the Kings of Britain, Chapter II). Later, in his Life of Merlin, Taliesin suggests to Merlin that they send for Arthur to come help repel the Saxons. However, Merlin says no for he foresees that God has allowed the Saxons to come and for the Britons to lose their nobility. This, however, only suggests that Arthur still lives, not that he will return. William of Malmesbury, a contemporary of Geoffrey goes a step further in his Chronicle of the Kings of England, ‘The sepulchre of Arthur is no where to be seen, when ancient ballads fable is still to come.’

In the book, Geoffrey claims that Arthur was taken to Avallon after his final battle with his bastard son Mordred and was healed, he writes ‘And even the renowned king Arthur himself was mortally wounded; and being carried thence to the isle of Avallon to be cured of his wounds, he gave up the crown of Britain to his kinsman Constantine, the son of Cador, duke of Cornwall, in the five hundred and forty-second year of our Lord’s incarnation’ (History of the Kings of Britain, Chapter II). Later, in his Life of Merlin, Taliesin suggests to Merlin that they send for Arthur to come help repel the Saxons. However, Merlin says no for he foresees that God has allowed the Saxons to come and for the Britons to lose their nobility. This, however, only suggests that Arthur still lives, not that he will return. William of Malmesbury, a contemporary of Geoffrey goes a step further in his Chronicle of the Kings of England, ‘The sepulchre of Arthur is no where to be seen, when ancient ballads fable is still to come.’

I give you all of this background to say this, we find ourselves today in need of Arthur. I recently gave a sermon at St Nicholas’ Church here in Nottingham, wherein I suggested that today we find ourselves in a struggle between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of the world. I couched this in terms I stole from C. S. Lewis; it is a struggle between Britain and Logres. Logres (or Llogres, or numerous other spellings) was the name for Arthur’s kingdom (Camelot was more of a capital city). I want to give the quote from Lewis’s That Hideous Strength I used in my sermon:

‘“It all began,” he [Dr Dimble] said, “when we discovered that the Arthurian story is mostly true history. There was a moment in the Sixth Century when something that is always trying to break through into this country nearly succeeded. Logres was our name for it––it will do as well as another. And then … gradually we began to see all English history in a new way. We discovered the haunting.”

‘“What haunting?” asked Camilla.

‘“How something we may call Britain is always haunted by something we may call Logres. Haven’t you noticed that we are two countries? After every Arthur, a Mordred; behind ever Milton, a Cromwell: a nation of poets, a nation of shopkeepers: the home of Sidney––and of Cecil Rhodes. Is it any wonder they call us hypocrites? But what they mistake for hypocrisy is really the struggle between Logres and Britain.”

….

‘“It was long afterwards,” he said, “after the Director had returned from the Third Heaven, that we were told a little more. This haunting turned out to be not only from the other side of the invisible wall. Ransom was summoned to the bedside of an old man then dying in Cumberland. His name would mean nothing to you if I told it. That man was the Pendragon, the successor of Arthur and Uther and Cassibelaun. Then we learned the truth. There has been a secret Logres in the very heart of Britain all these years: an unbroken succession of Pendragons. That old man was the seventy-eighth from Arthur: our Director received from him the office and the blessings; tomorrow we shall know, or tonight, who is to be the eightieth. Some of the Pendragons are well known to history, though not under that name. Others you have never heard of. But in every age they and the little Logres which gathered around them have been the fingers which gave the tiny shove or the almost imperceptible pull, to prod England out of the drunken sleep or to draw her back from the final outrage into which Britain tempted her.”

….

‘“So that, meanwhile, is England,” said Mother Dimble. “Just this swaying to and fro between Logres and Britain?”

‘“Yes,” said her husband. “Don’t you feel it? The very quality of England. If we’ve got an ass’s head, it is by walking in a fairy wood. We’ve heard something better than we can do, but can’t quite forget it … can’t you see it in everything English––a kind of awkward grace, a humble, humorous incompleteness? How right Sam Weller was when he called Mr. Pickwick an angel in gaiters! Everything here is either better or worse than––”

‘“Dimble!” said Ransom….

‘“You’re right, Sir,” he said with a smile. “I was forgetting what you have warned me always to remember. This haunting is no peculiarity of ours. Every people has its own haunter. There’s no special privilege for England––no nonsense about a chosen nation. We speak about Logres because it is our haunting, the one we know about.”

‘“Aye,” said MacPhee, “and it could be right good history without mentioning you and me or most of those present. I’d be greatly obliged if anyone would tell me what we have don––always apart from feeding pigs and raising some very decent vegetables.”

‘“You have done what is required of you,” said the Director. “You have obeyed and waited. It will often happen like that. As one of the modern authors has told us, the altar must often be built in one place in order that the fire from heaven may descend somewhere else. But don’t jump to conclusions. You may have plenty of work to do before a month is passed. Britain has lost the battle, but she will rise again”’ (That Hideous Strength, 367-8).

Sometimes I think this is something easier to talk about in the context of Britain but with Americans, but that is another issue for another day. What I really want to say is that as we struggle to help Logres win, it will often look like we’ve done very little.  After all, what made Logres itself so great is not the battles Arthur fought and won, it was the way life was lived in Logres. It was the feasting and celebrating that made Logres great. It was the virtue of his knights that made them great. It was the peace that ruled in the land. It was the dedication of everything that they did to the Lord.

After all, what made Logres itself so great is not the battles Arthur fought and won, it was the way life was lived in Logres. It was the feasting and celebrating that made Logres great. It was the virtue of his knights that made them great. It was the peace that ruled in the land. It was the dedication of everything that they did to the Lord.

At heart, I am an idealist. I believe in the incredible (literally, the unbelievable). I believe in Logres, which is to say that I believe in the kingdom of Heaven and I want to work to start the process of bringing it about before the return of Christ.

If Milbank is right and the return of Christ is the return of Arthur, or even if Arthur’s return is to come first, then I say with C. S. Lewis in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, ‘the sooner the better.’

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley

52.929830

-1.222213

This is one of those blogs that’s simply new to me. Josh Brockaway and haven’t properly met but were introduced over a mutual love for John Cassian. Collationes is one of the Latin titles for Cassian’s Conferences, Twenty-Four conversations held with Egyptian Monks in the Early Church. However, Collationes is not a dry and waterless place, but deals with many contemporary issues as well. Brockaway is an Anabaptist and often writes on a variety of theological topics. Some of his more recent posts include: Is Neo-Anabaptism a White Dude Movement?, Confessions of a Recovering Progressive, and Change without a Change.

This is one of those blogs that’s simply new to me. Josh Brockaway and haven’t properly met but were introduced over a mutual love for John Cassian. Collationes is one of the Latin titles for Cassian’s Conferences, Twenty-Four conversations held with Egyptian Monks in the Early Church. However, Collationes is not a dry and waterless place, but deals with many contemporary issues as well. Brockaway is an Anabaptist and often writes on a variety of theological topics. Some of his more recent posts include: Is Neo-Anabaptism a White Dude Movement?, Confessions of a Recovering Progressive, and Change without a Change. The final blog I want to feature today is one that in many ways probably doesn’t need it. Written by Artur Rosman, this blog has been featured or had its linked posted by so many others that my commendation here pales in comparison. Nevertheless, for those few who don’t read Artur’s blog, I definitely recommend it. Artur writes with cogency and authority on a variety of topics, including, poetry (particularly that of Czeslaw Milosz on whom Artur is writing his dissertation), Contemporary Roman Catholicism, imagination, theology, culture and more. Some of his more recent posts include, QUICK CATHOLIC CH-CH-CH CHANGES: POPE FRANCIS DOES A PHIL JENKINS, WHAT MAKES LITERATURE CATHOLIC?, and THIS FRIDAY’S DOSE OF RABELAISIAN CATHOLICISM.

The final blog I want to feature today is one that in many ways probably doesn’t need it. Written by Artur Rosman, this blog has been featured or had its linked posted by so many others that my commendation here pales in comparison. Nevertheless, for those few who don’t read Artur’s blog, I definitely recommend it. Artur writes with cogency and authority on a variety of topics, including, poetry (particularly that of Czeslaw Milosz on whom Artur is writing his dissertation), Contemporary Roman Catholicism, imagination, theology, culture and more. Some of his more recent posts include, QUICK CATHOLIC CH-CH-CH CHANGES: POPE FRANCIS DOES A PHIL JENKINS, WHAT MAKES LITERATURE CATHOLIC?, and THIS FRIDAY’S DOSE OF RABELAISIAN CATHOLICISM.