David Russell Mosley

Advent

12 December 2015

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Well, I’m behind on sharing this news by a few days, but for those who don’t already know: I am completely done with my PhD! In many ways I still can’t believe. In other ways, this is an unbelievably underwhelming time for me. It’s difficult to get too excited since everything has happened while I’ve been physically removed from the University of Nottingham (where I did my PhD).

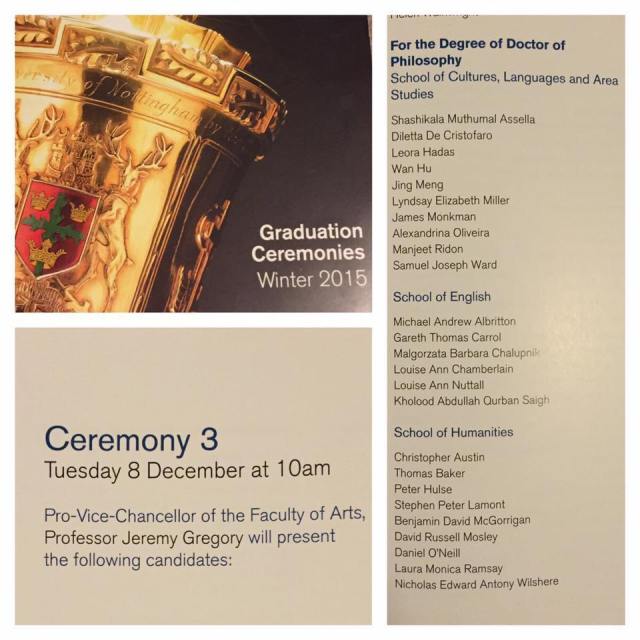

Last time I wrote you was right after I had passed my Viva. Since then, I had to resubmit my thesis with all the necessary corrections in October. I found out in mid-November that my corrections had been accepted. I was overjoyed at that news. There was a not-so-small part of me that worried I had not done enough, but evidently I had, for Rev. Dr. Alison Milbank (my internal examiner) emailed me a few days before the official word, telling me that she was happy to pass my thesis with the corrections I had made. Once I got the official word I had to get my thesis printed and bound and submitted to the appropriate people at the University. That was slightly difficult to manage from the States, but in the end it got done and I graduated, in absentia, on 8 December 2015, the feast of the Immaculate Conception.

As I said, I am overjoyed, but it has been a strange process. In a way, it has been a bit like becoming a husband or a father for me. That is, it is something that comes on gradually with new complexities at each stage. When does one become a father, after all? Is it when you find out your wife is pregnant? Is it when the baby is born? Or what about becoming a husband, after all, the process starts when you begin dating your spouse and changes once you become engaged, and changes again during the wedding ceremony, and changes once again on your wedding night. Becoming a doctor has been something like that. Was I a doctor when I passed my viva? Or when my corrections were accepted? Or when I graduated? And let’s not forget all the writing that went on before that, like dating before marriage, or having sex before conception. Becoming a doctor, of course, is not exactly the same as becoming a father or a husband, but the process, the gradualness of slowly passing stages that further your steps toward the end goal, that is the same.

Whatever the case, I am, unequivocally, and irrevocably, Dr. David Russell Mosley. I thank you all for your support, for your love, prayers, and interest during this process and while I wrote this blog, occasionally updating you on what I was doing toward getting my doctorate.

A final piece of news: As you already know, I am publishing a work of fiction with Wipf and Stock Publishers.

I am also pleased to announce, though this has been the case for some time, that I will also be publishing my thesis , Being Deified: Poetry and Fantasy on the Path to God, with Fortress Press in their Emerging Scholars series.

, Being Deified: Poetry and Fantasy on the Path to God, with Fortress Press in their Emerging Scholars series.

In light of all this good news, I could still use your prayers. I am still applying for jobs, teaching theology at the undergraduate and/or graduate level(s), but have not landed one yet. Please pray that one of the jobs I have already applied for, or, if not one of those, then one I will apply for in the near future, will come through and that I will be employed at an academic institution for the 2016/2017 school year. This is, perhaps, ambitious as many of my colleagues from Nottingham and elsewhere who have finished before me are still looking for work. Nevertheless, I pray for it for myself and for them and I ask that you do the same. In the mean time, I will continue to apply for jobs, write letters to you all here, and attempt to move forward with some new research topics. Until next time I remain,

Sincerely yours,

Dr. David Russell Mosley