David Russell Mosley

Eastertide

Octave of the Ascension

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

A few days ago a new acquaintance (really a kindred spirit and therefore friend, though we’ve not yet met) of mine, Michael Martin, wrote an essay on the Angelico Press blog entitled, “The Radical Catholic Reimagination of Everything.” For those unfamiliar with Martin, he is the Assistant Professor of English and Philosophy at Marygrove College and has written several works, the only one of which I have read thus far is The Submerged Reality: Ophiology and the Turn to a Poetic Metaphysics. Martin is like me, a believer in faërie, a poet (though a far better one as I understand it). I think we both can sign off on this line from an interview with theologian John Milbank, “I mean, I believe in all this fantastic stuff. I’m really bitterly opposed to this kind of disenchantment in the modern churches.” So I was overjoyed when Martin decided to put tires to pavement in a new way (he’s been living this stuff for some time now) when he wrote this essay.

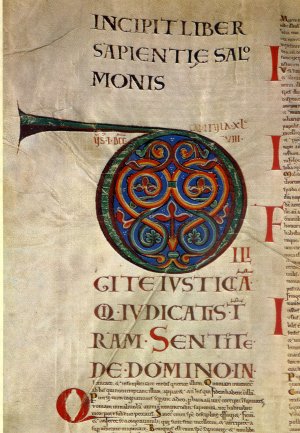

Martin’s essay is a clarion call to those who are like minded in this endeavor which he calls the radical Catholic (and I would add catholic) reimagination of everything, or one might it even call it the C/catholic unveiling of sacramental ontology, for, ultimately, this is what Martin is driving at. At the beginning, Martin, a proponent of sophiology (something on which I hope to write more as I understand more), notes the call to Wisdom (Sophia) that appears at key moments in the Byzantine Liturgy. He then turns to another part of the liturgy, a hymn called Megalynarion, “The Magnification of Mary.” You can read those for yourself in Martin’s essay. What I want to draw your attention to is this line from Martin:

“My investigation here is not about the liturgy, however, but about the ways in which phenomenology and sophiology discover the same phenomenon: the shining that illuminates the cosmos. This shining speaks in the languages of poetry, languages that take on a myriad of forms and are sometimes mistaken for science, sometimes for theology.”

Martin is calling us to a different way of seeing, but also a different way of doing, of being, simply put of living in reality. Martin understands that certain strains of theology do not allow for this kind of sight. He notes, via Hans Urs von Balthasar, that Neoscholasticism denuded itself of attention to the Glory of the Lord and that this proper attention was passed through certain poets, philosophers, and scientists while it was lost by the theologians. Even were one to disagree with this genealogy, one need only look at trends in theology today to see that this attention the Glory, to Sophia, to sacramental ontology has been ignored by many (though it is making something of return as theologians find themselves once again desiring to return to the sources).

In the end of his essay Martin issues a call to “poets, artists, scientists, adventurers, teachers, communitarians, distributists, scholars, and visionaries who hanker for something more living in Catholic culture.” He does not desire mere theory, men and women sitting in a room talking about how great it would be if. However, it should be obvious that Martin is not against the study of these issues in order to better inhabit these ideas and live this reality. Rather, Martin wants us to act as we talk. Theoretike and Practike must be united. Some may be Marthas and others Marys, but we need both and we need most of all those who are willing to live the hard life being both at once.

And so this is, in my own small way, my answer to Martin’s call. I am a poet, an author, a theologian, a gardener, a distributist, a husband, and a father (and more besides); I am all of those things bound up together and suspended as one made according to the Image. I am ready not simply to think about a sacramental ontology but to live it. This will be hard, already have I been confronting ways in which my habits did not accord with my beliefs and my knowledge, but I will answer this call. I must answer this call, I can feel it in the very blood that flows through me that this is right, that this is how reality really is. Confronting my son’s cancer was the first step for me in coming not simply to believe that these fantastic elements of the faith are true (I already believed), but to experience them. Yet I have let the shadows overcome me and make me believe that those moments are rare and that real life is lived without experience of the Glory. Well I say no more. I say that that way of living is ultimately damned (though we can be saved from it). Root and branch, twig and bough, I am in. Join me, as I join Martin and others and we radically (which remember means to return to one’s roots) and catholicly reimagine everything.

Sincerely,

David

The Quest has not failed, though Frodo had, by what the reader at least can call divine providence. Frodo and Sam are rescued and Middle Earth is free for a time, but the divine help needed in this moment foretells a future moment when providence will not be the course of action, but that God will step into his creation to set all things right.

The Quest has not failed, though Frodo had, by what the reader at least can call divine providence. Frodo and Sam are rescued and Middle Earth is free for a time, but the divine help needed in this moment foretells a future moment when providence will not be the course of action, but that God will step into his creation to set all things right.