David Russell Mosley

Festival of St Gregory of Nyssa and St Macrina

19 July 2013

Beeston, Nottinghamshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Today, I wanted to share another portion of my thesis. Sadly, this section neither features Gregory of Nyssa, nor his sister Macrina. Instead, it focuses on some work I’ve done concerning Thomas Aquinas’s Five Ways or Proofs of God and their relationship to deification. I hope you enjoy.

Thomas Aquinas’s Five Ways as Evidence of Deification

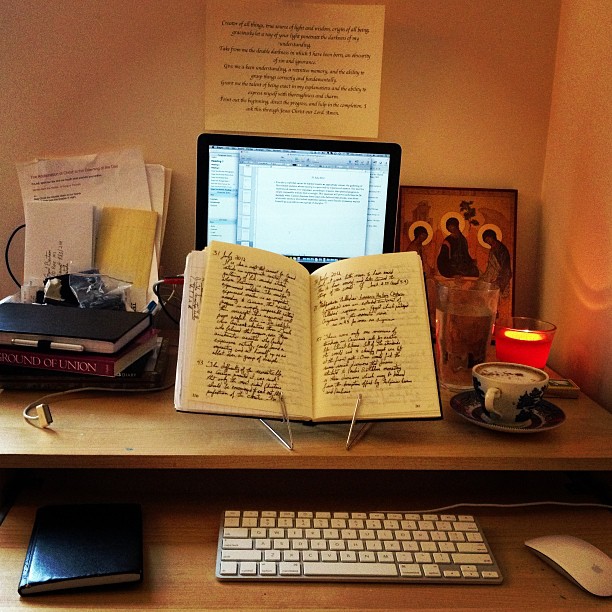

The fifth of Thomas Aquinas’ proofs of God’s existence was based on teleology (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

A. N. Williams in her work, The Ground of Union, suggests and demonstrates, ‘In seminal form, the Five Ways argue not only for God’s existence, but also the existence of a Thomistic doctrine of theosis.’1 For Williams, the Five ways do this first by creating a ‘deep ontological and conceptual divide,’ between Creator and creature.2 This provides safety from the danger that deification can have of appearing like pantheism. By showing how utterly other God is than his creation, the Five Ways not only disallow pantheism, but, in fact, allow for deification. This relates to one of our necessary categories for deification in the first chapter, namely, the Creator-creature divide. For Rudi A. Te Velde, ‘What Thomas is looking for [in the Five Ways] is not so much rational certainty as intelligibility; to wit the intelligibility of the truth expressed and asserted by the proposition “God exists.”’3 Thus, for both te Velda and Williams, the Five Ways are not intended as full blown proofs that God does in fact exist.4 The Five Ways show God’s connectedness and graciousness in sharing his own life, his very nature with his creation, especially the attributes, being, goodness, and perfection.5 Therefore, we shall take a brief look at the God described in the Five Ways to see the both the intelligibility of the God described and whether this God shows forth in this simple set of definitions is a God who deifies.

The first and more manifest way is the argument from motion. It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas a thing moves inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality. Thus that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it. Now it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold. It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God. (ST Ia. 2, 3)

In the first way, Thomas shows that change leads to God, that is, because things change, and change because of causes, there must be a ‘first cause of change not itself being changed by anything else’ (ST Ia. 2, 3). What Aquinas is doing here is, in one sense, showing the shortcomings of physics. Physics and natural science attempt to explain motion but cannot account for its existence.6 Thus Aquinas argues that for motion to exist there must be one who causes motion, is in fact, the first cause of all motion. As Te Velde notes, ‘The argument shows that being-in-motion, which is an essential feature of physical objects cannot be understood as being unless it is reduced to a first mover, which is itself not part of the domain of mobile being. As a consequence the domain of physics appears to be a finite domain, as being in motion cannot constitute the ultimate nature of reality.’7 This begins to build Aquinas’ implicit argument that there is a qualitative difference between God and creation. God is not merely a first or prime mover. If he were, then God would be just another thing within creation, even if greater than all other things in creation. Instead, at least as relates to motion, Aquinas posits God as being utterly different from all things that move/are moved.

This on its own is not enough to prove Williams’s point that the Five Ways show God as deifier, but this first way does show, as noted above, God as distinctly separate from creatures. Unlike all of creation, which is changeable, God is not changeable but is the first cause of all change. While not directly an argument for creation out of nothing, the first way shows forth a God that might create out of nothing. In fact, creation out of nothing would lead us to understand God as the first mover. As we saw in the previous chapter, for deification to work there must be a sharp distinction between Creator and creation. The first way leads us in that direction.

The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes. There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God. (ST 1a. 2, 3)

The second way is related to the first in that it focuses on causation. This time, however, Thomas wants simply to look at causation as such and not motion. Again, as with the first way, God is the source of all causation. If anything has a cause, it will be found ultimately in God. Here again, while all things in creation are caused and have effects, God is uncaused and is the source of all causation, creating a qualitative distinction between God and creation. The Creator-creature distinction is reiterated. The God described as both first mover and first efficient cause is a God utterly unique. It is a God that is not merely qualitatively different from creation. While we are not yet to the aspects of participation and analogy in Thomas’ thought at this point, clearly the God described in the first two of the Five Ways can lead toward the God in whom all things participate.

The third way is taken from possibility and necessity, and runs thus. We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated, and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence––which is absurd. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God. (ST 1a. 2, 3)

The third way shifts emphasis to necessity. Thomas reasons that all created beings are not necessary. If they are not necessary, then at some point they did not exist, for it is not necessary that they exist. This leads Thomas to question why there is anything at all then, for if nothing is necessary then at some point there was nothing at all. Therefore, there must be a being whose being is necessary in order to bring into being all unnecessary being. This necessary being is, again God. Thomas has now, in the first three ways, firmly established that God is completely and ontologically other than all creation. He is the only one who causes change without changing, who causes causation without being caused, and whose very being is necessary in order to bring all other being into existence. This third way begins to evidence to us deification. God as necessary being and the cause of all being is a God who shares himself with all unnecessary being, which is all other being besides himself.

The fourth way is taken from the gradation to be found in things. Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But “more” and “less” are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being; for those things that are greatest in truth are greatest in being, as it is written in Metaph. ii. Now the maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus; as fire, which is the maximum heat, is the cause of all hot things. Therefore there must also be something which is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection; and this we call God. (ST 1a. 2, 3)

Then, in the fourth way we see God defined as the something from which all being receives its perfection. Here again we have the hints of deification. The fourth way shows us a God who is the source of all comparison. When we say something is beautiful, it is only insofar as it relates to God who is the source of beauty. This would perhaps not be enough to give us a notion of deification if Thomas did not say, ‘There is something therefore which causes in all other things their being, their goodness, and whatever other perfection they have.’ Thus, God is not solely the source of comparison, he is also the cause of perfections in created beings. As both source and cause of perfection, the God described in the fourth way is a God who shares of himself with his creation. This is a God who would be likely to deify.

The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world. We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God. (ST 1a. 2, 3)

Finally, in the fifth way we reach what is often called the teological argument, that is, everything in nature has a goal for which it is intended and God is the director who directs created beings to their telos, their end. While Thomas does not make it evident here, this end is God himself (cf. ST 1a. 44, 4). Thus not only does the fifth way describe a God who progressively perfects his creation to an end, but it suggests that the end described is God himself. Thus again, we see the evidence that the God described in the five ways is a God who would deify.

This skeletal depiction of God is one of a God who seems to desire to make creatures and then make them more like himself. By being truly distinct from his creations, God can make them more like himself. By being their mover, their first and final cause; indeed by making them partakers of himself, the God described in the Five Ways is a God who deifies, perhaps at varying levels, his creations at least in part because he created them.

1 A. N. Williams, The Ground of Union: Deification in Aquinas and Palamas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 41.

2 A. N. Williams, The Ground of Union: Deification in Aquinas and Palamas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 40.

3 Rudi A. Te Velde, Aquinas on God: The ‘Divine Science’ of the Summa Theologiae (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), 39.

4 Despite Anthony Kenny, The Five Ways: St. Thomas Aquinas’ Proofs of God’s Existence (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969).

5 A. N. Williams, The Ground of Union: Deification in Aquinas and Palamas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 41.

6 Rudi A. Te Velde, Aquinas on God: The ‘Divine Science’ of the Summa Theologiae (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), 51.

7 Rudi A. Te Velde, Aquinas on God: The ‘Divine Science’ of the Summa Theologiae (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), 55.

Let me know what you thought.

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley