David Russell Mosley

Epiphanytide

22 January 2015

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

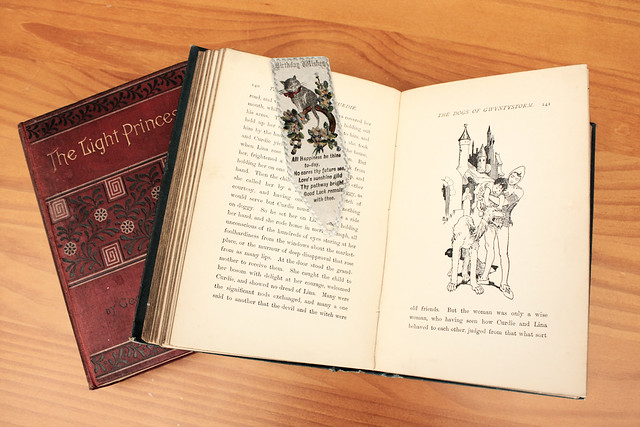

George MacDonald’s fairy tale, ‘The Light Princess’ is one of my favourites amongst his fairy tales. In many ways, it is a retelling of Sleeping Beauty. Let me explain. The story begins, very similarly with a king and queen who cannot have, but want, a baby. They are much sillier than the king and queen in sleeping beauty, but they are generally good people. So, eventually, a baby they have.

After the baby is born they begin planning the christening. Now, it’s true that there are no fairies invited to this christening, nor is anyone invited to be the little princesses godmother. I think, however, this is because MacDonald wants to provide her with two very different godparents: Princess Makemnoit, the little girl’s aunt who was not invited, by accident, to the christening; and God himself. Let me explain.

Like in Sleeping Beauty, Princess Makemnoit, who is a witch (and potentially a fairy as MacDonald writes, ‘she beat all the wicked fairies in wickedness, and all the clever ones in cleverness’), decides to revenge herself on the king for forgetting her. When she arrives, ‘she contrived to get next to [the baptismal font], and throw something into the water; after which she maintained a very respectful demeanour till the water was applied to the child’s face. But at that moment she turned round in her place three times, and muttered the following words, loud enough for those beside her to hear:—

“Light of spirit, by my charms,

Light of body, every part,

Never weary human arms—

Only crush thy parents’ heart!”‘

The witch deprives the little girl of all her gravity, in both senses. She is not directed downward and most all other creatures are and she has no gravitas, no sense of the grave or serious. It is telling that this is the only “gift” the princess receives on this day. And so the princess grows up, always laughing, never smiling. Even her levitas was incomplete, because it lacked gravitas.

Unlike Sleeping Beauty, this princess has had no godmother, fairy or otherwise to give her gift that will undo Princess Makemnoit’s curse. In Sleeping Beauty’s case, the final fairy godmother gives her the possibility of finding love. But in the Light Princess’s case it is the curse that leads her to love. In fact, first it leads her to water and then leads her to love. Princess Makemnoit is not only the cause of the undoing of the princess’s curse, by draining the water of the lake and causing the prince to give his life for the Light Princess, but she is also her own undoing. And so, Princess Makemnoit does good for the Light Princess. She teaches her gravitas, she gives her a reason to cry. She gives her, a bit delayed perhaps, a good gift, the gift of balance between gravitas and levitas that makes happiness and joy possible.

Up to this point, I have looked at Princess Makemnoit as an Unintentional Godmother, she is, after all, the only one who gives anything to the child on the day of her baptism. However, I think there is clearly another godparent. God is clearly present in this story, working like a godparent to the Light Princess from the first. It is he who makes it possible for the curse of Princess Makemnoit to ultimately lead to love. It is he who avenges himself and nature on Princess Makemnoit by the use of nature itself. What is more, Princess Makemnoit sins against the waters of baptism by defiling them before the princess is baptised. It is fitting then, that the mode of her destruction should be water itself. For further proof that God is the unseen godparent of the Light Princess, notice that it is in water itself that the Princess regains her right relationship with gravity. Water was the means of her curse, but it was also the means of her salvation and redemption, both in her baptism, and in the death of her love.

So, in the end, George MacDonald’s ‘The Light Princess’ gives us a very interesting look at godparenthood in fairy tales. Rather than give his Princess a fairy godparent (or at least giving her a good one), she receives instead God himself as her godparent.

Sincerely yours,

David