David Russell Mosley

Ordinary Time

St Cyril and St Methodius

14 February 2015

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Ever since we spent all that time in the hospital for Edwyn’s cancer treatment, I’ve been meaning to write this post. Tonight, another minor vision, more of a palpable sense than a vision, has finally been the impetus to do so.

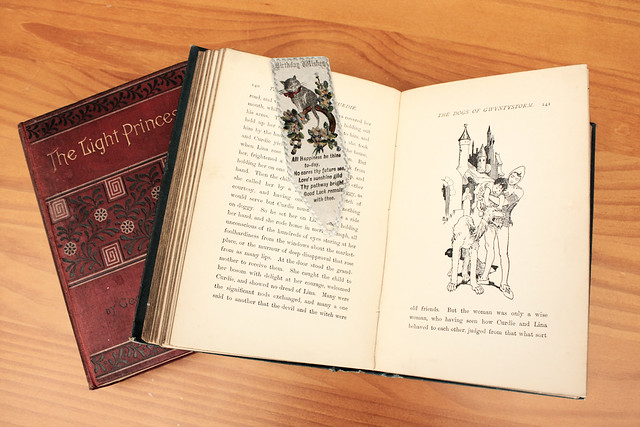

I noticed it first when we were in our first room when the cancer treatment proper began. Both of my sons had an obsession. They loved to look at light. When the sun would pour in as it began to set. While we adults would shield our eyes, my sons soaked it in, preferring to look at what it illumined in contrast with what it did not. Shadows and light were their delights, often catching their attention. Little has changed in this regard. Now, however, rather than being merely content to watch light, they seek it out and attempt to grasp it. So often when the sun shines (and it almost always the sun or a reflection of it that they are attracted to, not artificial light) and lands on their highchair trays will they try to grasp it. Or when the sun is reflected off a watch or a phone or something similar they will gaze upward as it moves across the ceiling and the walls. It reminds me of a portion of one of George MacDonald’s fairy tales.

The whole fairy tale is ultimately about light and the love of light in its varying shades. The story is about a witch who raises a boy and girl, quite separately from one another. The girl knows only night and the boy only day from infancy. While both have an obsession with light, the girl’s is stronger. She falls in love with the moon, her lamp as she calls it, and is confused when it is gone one day. So she decides to go in search of it:

‘She followed the firefly, which, like herself, was seeking the way out. If it did not know the way, it was yet light; and, because all light is one, any light may serve to guide to more light. If she was mistaken in thinking it the spirit of her lamp, it was of the same spirit as her lamp and had wings. The gold-green jet-boat, driven by light, went throbbing before her through a long narrow passage.’

I’ve always been drawn by this passage. MacDonald gives us here a kind of participatory ontology (as he usually does, he is very much a Platonist). This little insect is thought of as made of light ‘it was yet light’ and also ‘driven by light’. Light is its being and yet is also its source and its power of motion. What is more, there is the light out of which the firefly is made is derived from a more ultimate, and in this story, unnamed Light. C. S. Lewis describes Christianity by comparing it to the sun. He believes in it not because he see it but because by it he can see everything else. All of this is, I believe, my sons’ love of light.

This brings me to tonight. Every night when we put our boys in their cribs, I sing them a lullaby; read them a bed time story; and pray for them. My prayer for my sons usually goes something like this: ‘Heavenly Father, be with my sons this evening. Send them your Holy Spirit to guide them and give them dreams and visions; send your angels to watch over them and protect them from the fears and dangers of the night. Blessed Virgin, watch over my sons as you watched over your own Son, Jesus Christ, our Lord.’ Tonight however, I was led to pray more. I began to feel an unbearable lightness. I could sense the saints and angels present with me in that room. So I prayer: ‘Saints and angels in this room, praise our heavenly king with me: Holy, Holy, Holy Lord, God of power and might, Heaven and Earth are full of your glory.’ I began to weep. The sense of their presence, of God’s presence through his created cosmos which includes the angels and the saints was unbearably light (God, as Dionysius would remind us, is full of these paradoxes).

Light has two meanings here: the radiance of a creature; and of little or no weight. Yet I think they are connected. For the light of the sun is unbearable, not because of its weight but because of its brilliance. While I saw no light during my prayer this evening, it was nevertheless brilliant and it was unbearable for a sinner such as me.

Sincerely yours,

David