David Russell Mosley

Eastertide

7 April 2016

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Last week, Image Journal, posted to their blog an essay by Christiana N. Peterson. In the essay, Peterson talks about her daughter’s longing for fairies and its relation to the mystics longing for God. I posted the article to my personal Facebook page saying, “There is more that could be said, but this is a good beginning.” Today, I would like to say a little more.

Some of my friends responded to the article noting that the depiction of mystics was rather sanitized and romanticized. This is true. Peterson writes:

The mystics’ words make me think of wings again, of living in the trees of Middle Earth with the elves. Why, I wonder, would reading the mystics feel like reading Tolkien or searching for fairies in the dying light of summer?

I so want to encounter God in the way of the mystics. I want to know God is with me, right now in the moment, in tangible, visible ways. So I pour over their words and spiritual practices, wishing to have visions but knowing that God often comes to us in more mundane ways.

For Peterson, reading the mystics is like reading Tolkien, but I’m not sure if it’s like reading Tolkien in the right way. For Peterson, the connection is between the deeper realities glimpsed by the mystic and a land populated with things like elves, dwarves, and dragons. Yet when I read the mystics, I feel less like I’m reading Tolkien, in that sense anyway, and more like I’m reading Ezekiel or Dante or Tolkien in a very different sense. Let me explain.

The mystics, who really can’t be categorized together like this, are often giving us insight to one of two things if not both. Often they are giving us translated visions of the deeper reality, of the angels, thrones, and powers, the logoi that stand behind and uphold, through God, the things we experience everyday. Or else they give us an insight into ourselves. Peterson mentions Theresa’s interior castles, but it is precisely that these are castles that exist within us. I think of Augustine’s Confessions where he turns from searching for God in creation to searching for God within himself and as he plumbs the depths of his soul is raised to higher heights. Or again, I think of Dante who takes us through Hell (our own sinfulness), purges us in Purgatory, and gives us that first glimpse of the Beatific Vision and the ecstatic understanding that will be given to us on how God could be so joined to man in the person of Jesus Christ, by extension (or better participation) in us. Or again, I think of Denys and how the Celestial Hierarchy stands behind, upholds, and gives reality to the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy.

For me this reminds me of Tolkien not because of Middle-earth, per se, but what Middle-earth represents, namely the reality of Faërie. Tolkien writes in On Fairy-stories, “It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of words, and the wonder of things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.”1 I’ve written before about this, and other, quotations from Tolkien’s On Fairy Stories, but I want to draw attention to this line again because of the examples Tolkien uses. It is perhaps not inappropriate to see in bread and wine the Eucharist. Here, in a way, we get at the heart of the mystics. For many mystics things we see in everyday life, or fantastical combinations of them (e.g., the griffon), stand for deeper, spiritual realities. They images that serve as symbols of a deeper reality. In the Eucharist (and other sacraments) it is not just pictures but physical objects themselves that serve as real symbols of deeper realities.

What is more, however, is that for Tolkien, Faërie itself is the Perilous Realm. A land in which, should we venture, we will not come out unchanged (as Aragorn says to Boromir before they enter Lothlorien). If, as a friend has suggested, Peterson’s view of mystics is sanitized, so too is her picture of Faërie. The angels, it would seem, are terrifying to behold, if we take seriously their injunctions to “Be not afraid” when they appear to mortals. Lewis uses this to an interesting effect in his Perelandra when the two guiding intelligences of the planets Mars and Venus ask Ransom, the human protagonist of the Cosmic Trilogy, to tell them which will form will be most suitable for introducing themselves to the King and Queen of Venus. Ransom is terrified as they appear to him in forms whose depictions are lifted almost word for word out of Scripture (notably Ezekiel).

Now, like Peterson, I will be raising my children to look for fairies, though perhaps not in broken potsherds, but in large mounds. I hope that this investment in their imagination will do for them what it did for me, open up the possibility that there are things we cannot see or cannot comprehend and categorize. That along with angels and the logoi (insofar as those two are separable) there may be lesser beings both like and unlike us who belong to this world in a way even we do not, and that we might be able to catch a glimpse of them if we correct our vision (which often takes holiness). Yet I hope my children will also learn to seek these things in the right spirit, the spirit that says these things are not safe, they are not tame, to borrow language from Lewis, but that at least some of them are good.

So, I agree with Peterson, there is a connection fairies, or better Faërie, and Mystics. But this connection has to have the right tenor, the right level of both levitas and gravitas. We can at once find both joy and terror in the presence of God, so to in the Perilous Realm, and we need both in order to see them more clearly. A joyless God is not a God worth our worship and yet neither is one who does not inspire us to say, “Woe is me, I am a man of unclean lips.” What we do not need are safe fairies, nor a safe God. Safe reality is not worth our existence. We need stories and a reality that rightly reflect the deeper truths. Consider again the Eucharist. Here is the source, in so many ways, of all our joy. We are united to Christ as we eat his flesh and drink his blood. Yet consider precisely what we are doing, we are eating flesh and blood. We are re-visiting not only the night on which Jesus was betrayed, but his crucifixion, his body torn, his blood poured out. The source of all our joy is a moment of horrific torture unto death. This is something the mystics most certainly understood as their visions make clear (I think of St. Perpetua and her dream about the ladder covered in nails and spikes with a dragon at its base. Yet once she reaches the top, there is joy and peace). It is both levitas and gravitas, life and death, joy and danger, that unites our search for fairies and our search for God and the deeper truths of reality.

Sincerely,

David

1 J. R. R. Tolkien, ‘Tree and Leaf,’ in The Tolkien Reader (New York: The Ballantine Publishing Company, 1966), 78.

This is one of my annual Advent/Christmas reads. If you’ve never read it, or if you’ve never read a book by an ancient Christian, then I recommend it, especially this translation. The Popular Patristics Series (patristic means relating to the early Christian theologians, often called the Church Fathers) by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press is a great series for getting translations of ancient texts in understandable English. However, it’s also a great series for the scholars out there. If you are a scholar or are interested in getting into the original languages then I’d recommend picking up

This is one of my annual Advent/Christmas reads. If you’ve never read it, or if you’ve never read a book by an ancient Christian, then I recommend it, especially this translation. The Popular Patristics Series (patristic means relating to the early Christian theologians, often called the Church Fathers) by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press is a great series for getting translations of ancient texts in understandable English. However, it’s also a great series for the scholars out there. If you are a scholar or are interested in getting into the original languages then I’d recommend picking up  This is the other theological book I’m reading right now. I picked up at the recent AAR/SBL and have become acquaintances with the author. Now, my reading of Hans Urs von Balthasar has been fairly limited, but that’s not an issue with Carpenter’s book. She explains Balthasar’s thought very clearly so that you get a sense of what he’s saying without having read all the books and essays Carpenter has. That said, this is a definitely an important book in Balthasarian scholarship. Carpenter, so far anyway, is doing an excellent job explaining the importance of art and poetics to Balthasar’s theology. While she uses the word theo-poetics differently than I do in my thesis, her use is, I think still connected. For Carpenter, theo-poetics is about a poetic theology, poetic logic and images that help undergird and connect theological reflections (whereas my own use is to connect it directly theopoiesis or deification). So far the only glaring problem with this book is that it is making me want to buy more Balthasar books than I can presently afford.

This is the other theological book I’m reading right now. I picked up at the recent AAR/SBL and have become acquaintances with the author. Now, my reading of Hans Urs von Balthasar has been fairly limited, but that’s not an issue with Carpenter’s book. She explains Balthasar’s thought very clearly so that you get a sense of what he’s saying without having read all the books and essays Carpenter has. That said, this is a definitely an important book in Balthasarian scholarship. Carpenter, so far anyway, is doing an excellent job explaining the importance of art and poetics to Balthasar’s theology. While she uses the word theo-poetics differently than I do in my thesis, her use is, I think still connected. For Carpenter, theo-poetics is about a poetic theology, poetic logic and images that help undergird and connect theological reflections (whereas my own use is to connect it directly theopoiesis or deification). So far the only glaring problem with this book is that it is making me want to buy more Balthasar books than I can presently afford. This is another of my annual Advent/Christmas reads. Tolkien, that wonderful sub-creator, began writing his children letters from Father Christmas in 1920 when his eldest son, John, was three years old. From that first simple letter comes many more with more and more characters and events each year for the next 26 years (he stopped when his daughter Priscilla was 17). These letters are full of wonderful stories, as you can well imagine, but also wonderful pictures. Tolkien was a rather good artist in his own way and the pictures as well as samples of the handwritten letters that adorn this book are wonderful in the truest sense of the word.

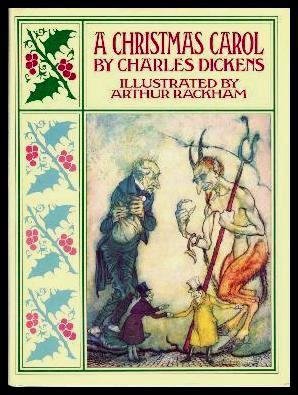

This is another of my annual Advent/Christmas reads. Tolkien, that wonderful sub-creator, began writing his children letters from Father Christmas in 1920 when his eldest son, John, was three years old. From that first simple letter comes many more with more and more characters and events each year for the next 26 years (he stopped when his daughter Priscilla was 17). These letters are full of wonderful stories, as you can well imagine, but also wonderful pictures. Tolkien was a rather good artist in his own way and the pictures as well as samples of the handwritten letters that adorn this book are wonderful in the truest sense of the word. Yet another of my annual Advent/Christmas reads, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is really a book everyone should read, full stop. In this book both the meanness, the grotesque, the worst of human nature and the best are on display. Dickens perhaps knew people, and possibly even humanity in general, better than almost any other author (Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Tolkien, and a few others would perhaps also vie for this honor). In this book we get a glimpse into dark recesses of fallen human nature and even a reminder that we cannot crawl out of those recesses completely on our own. The story has, it’s true, become perhaps a bit too familiar to us with umpteen different versions of it in existence on the big and small screen. Still, if you can, try to read the story with fresh eyes and I will be much surprised if you don’t come away having been changed by the story.

Yet another of my annual Advent/Christmas reads, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is really a book everyone should read, full stop. In this book both the meanness, the grotesque, the worst of human nature and the best are on display. Dickens perhaps knew people, and possibly even humanity in general, better than almost any other author (Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Tolkien, and a few others would perhaps also vie for this honor). In this book we get a glimpse into dark recesses of fallen human nature and even a reminder that we cannot crawl out of those recesses completely on our own. The story has, it’s true, become perhaps a bit too familiar to us with umpteen different versions of it in existence on the big and small screen. Still, if you can, try to read the story with fresh eyes and I will be much surprised if you don’t come away having been changed by the story. For the last few years when I decided I wanted to read through the Sherlock Holmes stories, I would pull out a single-volume edition of the complete stories that I have (it’s a facsimile edition from the originals in the Strand Magazine) and attempt to read them. I say attempt because the book is massive and the pages fragile. So, this year, after reading half of A Study in Scarlet in this format I decided enough was enough, popped over to the library, and picked up several smaller volumes in order to read all the stories without the pain of using my beautiful, but unwieldy single-volume edition. If you’ve never read Holmes, I highly recommend it. These stories are witty, interesting, full of life. I will give a warning however, the majority of the second half of A Study in Scarlet is generally uncharacteristic for the rest of the Holmes stories, taking place in America and having nothing directly to do with the primary protagonists, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson.

For the last few years when I decided I wanted to read through the Sherlock Holmes stories, I would pull out a single-volume edition of the complete stories that I have (it’s a facsimile edition from the originals in the Strand Magazine) and attempt to read them. I say attempt because the book is massive and the pages fragile. So, this year, after reading half of A Study in Scarlet in this format I decided enough was enough, popped over to the library, and picked up several smaller volumes in order to read all the stories without the pain of using my beautiful, but unwieldy single-volume edition. If you’ve never read Holmes, I highly recommend it. These stories are witty, interesting, full of life. I will give a warning however, the majority of the second half of A Study in Scarlet is generally uncharacteristic for the rest of the Holmes stories, taking place in America and having nothing directly to do with the primary protagonists, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson. The first of those books is The Blue Fairy Book by Andrew Lang. This is the first in a series of books that are collections of fairy-tales and folk stories from around the world. When I first started writing my novel 8 years ago, it was to this series of books that I turned reading every story about dwarves, goblins, elves, brownies, and more to try and ground my characters and creatures in the stories we have told ourselves about them.

The first of those books is The Blue Fairy Book by Andrew Lang. This is the first in a series of books that are collections of fairy-tales and folk stories from around the world. When I first started writing my novel 8 years ago, it was to this series of books that I turned reading every story about dwarves, goblins, elves, brownies, and more to try and ground my characters and creatures in the stories we have told ourselves about them. The second book on the back burner is The Shaping of Middle-earth by J.R.R. Tolkien. This is the fourth book in the History of Middle-earth Series put out by Christopher Tolkien. This particular volume takes through the stories as things begin to shift from Book of Lost Tales version of them to The Silmarillion version. This isn’t a great book (nor are any in the series) to serve as your “fiction read” if you divide up your reading like I do. That said, the stories in them are always fascinating, as is the insight we’re given into how Tolkien wrote and how his stories developed over time.

The second book on the back burner is The Shaping of Middle-earth by J.R.R. Tolkien. This is the fourth book in the History of Middle-earth Series put out by Christopher Tolkien. This particular volume takes through the stories as things begin to shift from Book of Lost Tales version of them to The Silmarillion version. This isn’t a great book (nor are any in the series) to serve as your “fiction read” if you divide up your reading like I do. That said, the stories in them are always fascinating, as is the insight we’re given into how Tolkien wrote and how his stories developed over time.